Vickie Sorensen talks about her father at 20:00 and 42:35.

Category: Miscellaneous

Epilogue – Talking Old Soldiers

Frank Sorensen

Why hello, say can I buy you another glass of beer

Well thanks a lot that’s kind of you, it’s nice to know you care

These days there’s so much going on

No one seems to want to know

I may be just an old soldier to some

But I know how it feels to grow old

Yeah that’s right, you can see me here most every night

You’ll always see me staring at the walls and at the lights

Funny I remember oh it’s years ago I’d say

I’d stand at that bar with my friends who’ve passed away

And drink three times the beer that I can drink today

Yes I know how it feels to grow old

I know what they’re saying son

There goes old man Joe again

Well I may be mad at that I’ve seen enough

To make a man go out his brains

Well do they know what it’s like

To have a graveyard as a friend

`Cause that’s where they are boy, all of them

Don’t seem likely I’ll get friends like that again

Well it’s time I moved off

But it’s been great just listening to you

And I might even see you next time I’m passing through

You’re right there’s so much going on

No one seems to want to know

So keep well, keep well old friend

And have another drink on me

Just ignore all the others you got your memories

You got your memories

Written by Vicki Sorensen

During my adolescence in the 1970’s, my favourite recording artist was Elton John. One song in particular entitled Talking Old Soldiers caught my attention. It seemed to frame the musings and bewilderment I had about my father, a World War II Air Force veteran and prisoner of war.

I knew my father’s struggle with alcoholism was the outcome of his military service, but my understanding was limited. I certainly made no connection between his angry outbursts and wartime trauma, and over the years I came to resent the unpredictability of his mood swings, and the feelings of being let down every time I saw him with a case of beer.

I was fearful of how my father would react if I asked questions about the war, so I just followed what I thought was my parents’ lead. Don’t talk and don’t ask questions about the war. I wanted to play that song, Talking Old Soldiers for my father, but apprehension overrode my wish to reach out. Would he be mad? Would he break down? Would he start drinking? Would he have a nightmare? Then I would have to deal with my mother’s ire for triggering an episode. I had seen a few and didn’t want to be the cause of one.

As a young child, I learned to tread lightly and keep a low profile. One occasion however, poor judgement lured me into sneaking up on my father and scaring him. I got the blast of my life and as I was slinking away to pout, he did something unusual. My father offered an explanation. He asked me to imagine what it would be like to have bombs going off all around you, and once it was over, discovered you had tried to dig a hole in the ground with your bare hands. Lack of knowledge about my father’s war left me wondering how he would have been in a situation to be bombed. A missed opportunity to open Pandora’s Box, but I was only 10.

I thought many times, the song Talking Old Soldiers could be a catalyst. To what, I wasn’t sure. I imagined myself approaching him, asking if he would like to listen to this song. I thought about the lyrics that may ring true for him, as the aging veteran in the song conveys he’s “seen enough to make a man go out his brains” and wonders if “they know what it’s like to have a graveyard as a friend.” He laments about knowing how it feels to grow old and I wondered if my father thought about fallen comrades who did not grow old.

I envisioned my father weeping at the song’s end. “How could you,” I feared he would say. I lacked the courage to be a strong shoulder. Would he have told me about the friends he lost while a prisoner of war after a mass escape attempt from Stalag Luft III. That the anger he wore on his sleeve was a result of the execution of these friends. Perhaps an exposition of painful memories would have also led to an understanding of my father’s aversion to loud noises. Towards the closing stages of the war, POWs were forced to march hundreds of miles west across Germany during the winter and spring. They were targets of friendly fire which included strafing and bombings from the allied Air Force. I can only speculate it was during one of these fly bys my father found himself scrambling in a futile attempt to dig a hole that would offer no protection from the onslaught.

Talking Old Soldiers represents a wasted chance to set right the misunderstandings that marred our relationship. I think about the only Remembrance Day service my father and I attended together, three months before he died. His reticence gave little clue as to what he was thinking, how he was feeling, and I didn’t ask. Knowing now what I didn’t know then, I believe my father was simply going through the motions of laying a wreath at the service’s memorial. In his mind’s eye, he was overseas in Poland, laying his wreath at the Memorial to the 50; “In Memory of the Officers Who Gave Their Lives.”

Drawing by Ley Kenyon – September 1944

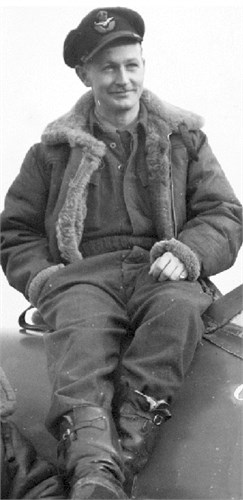

Frank Sorensen

If you wish to contact us, please leave a comment or fill out this form below.

Trafalgar Square in Wartime

Note

Vicki Sorensen shares what her grandfather Marinus Sorensen wrote after the war.

Trafalgar Square in Wartime

From my window where I worked I looked out over Trafalgar Square. It gave me a kind of box seat to the play “London in the War Years.” From third floor heighth I watched the stream of people down there and from the roof of the Canadian Pacific Building in the watches of the night when the air raid warning sounded I saw death, suffering and destruction rained down over the city. Without realizing what was happening or what was at stake, there from my window I saw glimpses of the Battle of Britain when the few repelled the many and inflicted the first defeat on the German Luftwaffe.

The stream down on the square, its one way traffic comes from Whitehall and The Strand. It passes Canada House corner, the National Gallery into Charing Cross Road or The Strand. Right before me when I looked out was the National Gallery with its domed roof. Over in the corner was St. Martin-in-the Fields. To the left, Canada House, with Canadian Military Headquarters next door, and to the right, South Africa House. Then, if I turned around and looked out to the Admiralty Arch and the Admiralty. Such is the layout of Trafalgar Square. In the centre is the monument. The Nelson Column towers up and is like a beacon to the stranger; a landmark to help you spot your bearings. More soldiers have been photographed by the lion, grouped around the column than anywhere else. The whole American army was there – and Canadians too. Or the photographer would put a few grains of corn in their hands and took them while the pigeons were sitting on their outstretched arm. A much favoured position for photos. Weather would have to be very bad if the pigeons and the photographer could not gather a ring of onlookers.

Trafalgar Square was truly the hub of the Empire. Yes, more than that, the centre of the world. Here, commences Whitehall with its many historical buildings. From the Nelson Column to Big Ben with side streets like Scotland Yard and Downing Street. I blew in from Petsamo in the Artic in June 1940 and was there until 1946. Thus, I had a fine observation post during the war. For if you cannot be with your own, where would be a better and more interesting place than London. I was there when the bells were silenced when they became bells of warning to tell us that the enemy was invading the land. I was there too when that danger was over and they could ring joy and relief and thankfulness over the land. We heard them often from St. Martin’s. Perhaps you would see a crowd on the steps to the church waiting to see the bridal couple. But that would also change to a different mood when sorrow had its hour. As when the 50 Airmen from Stalag Luft III were murdered. Stalag Luft III where my own boy, if all was well was imprisoned. All was well, and he’s back again.

For the greater number of people who come to it, St. Martin’s is for moments of meditation and prayer. It’s a week day church, it’s on a busy thoroughfare and during the war years its crypt was used as a lunch canteen. Church services are not only hymns and rituals and preaching, it’s also the good we can do to help. The help we can give our neighbour, the improvement that we can bring into our community. “Love a neighbour” had good soil in England during the war. In our danger it grew whether it was implemented by the authorities or it was service my neighbour rendered me.

Well do I remember St. Martin’s on D-Day? For years had we seen the preparations and long had we waited for the day? Now it was as if everything was at stake. The great concentration of our strengths which was to be the beginning of the end. The end that would bring relief to suffering millions. The end that would set prisoners free and unite families again. We were told that all was well but it was a solemn gathering at the church. It was as if people understood one another so well. Your son and my boys – are they not there. When they were born it was a gift of God. There for the good fight and its well that a day like this we should come here in humble prayer for our country’s cause and for them. That day short services were held in factories and places of work and in all the churches of the land. It was all prepared beforehand. Only the date was unknown. And when victory and peace came did we give thanks and praise as fervently as we prayed? I think so.

As clouds continually change the picture of the sky, so with Trafalgar Square the frame and the setting is the same but life is changing. New people move in on the stage continually. London was not only the capital of England and a centre of the empire, it was headquarters for the free world and the hope of the oppressed was ever focused on London. Here on Trafalgar Square was reflected the help that came. The Americans, Canadians, Australians, South Africans, the forces of New Zealand, India and Newfoundland. There was not a colony so small that it was not there. Even St. Helena and lonely Tristan da Cunha sent their young men, and there were the soldiers from France, Norway, Holland, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Belgium, Yugoslavia and even from my own native Denmark. London was a milestone on their way and Trafalgar Square was the rendezvous for friends.

Here from my window was much to see. Processions, parades and demonstrations. Soldiers on their way to the front, soldiers coming on leave. From Trafalgar Square the great war loans were launched with many speeches and much display. The war had taught people to queue and they even learned to queue for war loans. My impressions of Trafalgar Square are many and varied. But strongest perhaps is the impression of a tall young man in civilian dress with a raincoat over his shoulder in a manner of the navy. It was clear that he must be a naval officer. From Monday to Saturday of one week he came at a quarter to eleven, kneeled at a column, the Nelson Column and when Big Ben struck eleven, he rose and walked away. This was in the darkest hours of the war. Did he come to the Nelson Memorial for inspiration, to dedicate himself to a task allotted to him? I believe so, and I thought well fought country with such warriors.

All poets have been prophets. In Milton, Shakespeare, Blake, Shelley, Tennyson and many others we have evidence of their preview of things to come. But Victor Hugo had also visions of England. He’s alleged to have written the following in his exile in the Channel Islands:

“Over that sea in calm majesty lies the proud island whose existence consoles me for a thousand continental crimes and vindicates for me the goodness of Providence. Yes, yes, proud Britain, thou art justly proud of thy colossal strength – more justly of thy God-like repose. Stretched upon the rock – but not like Prometheus and with no evil bird to rend thy side rests the genius of Britain. He waits his hour but counts not the hours between. He knows it’s rolling up through the mystic hand of destiny. Dare I murmur that the mists will clear for me, that I shall hear the rumbling wheels of a chariot of the hour of Britain. It will come – it’s coming – it has come! The whole world, aroused as if by some mighty galvanism, suddenly raises a wild cry of love and admiration, and throws itself into the bounteous bosom of Britain. Henceforth there are no nations, no people, but one and indivisible will be the world, and the world will be one Britain. Her virtue and her patience have triumphed. The lamp of her faith, kindled at the apostolic altars, burns as a beacon to mankind. Her example has regenerated the erring, her mildness has rebuked the rebellious, and her gentleness has enchanted the good. Her type and her temple shall be the Mecca and Jerusalem of a renewed universe.”

What a glorious vision. I could end with nothing better.

If you wish to contact us, please leave a comment or fill out this form below.

Diary Entries – June 1, 1945

Note

Vicki Sorensen shares her grandfather’s diary entries after her father’s liberation and return to England.

June 1, 1945

The war in Europe ended 8th May and we had two days of Peace or rather Victory celebrations. For GC and I it was two days of rest. We had a hot spell of weather and it was all very agreeable. Streets were decorated with the material at hand, chiefly from the Coronation and bonfires were lit in the evenings. People were happy and relieved but there would also be the lonely heart with a dear one not returning. There was a steady stream of Bombers over our heads in these days, flying our men back from German prison camps. We looked at them and wondered if our Frank was there.

Frank actually landed in England on the 9th May – Wednesday. He telephoned to me, or tried to, on the day following and Saturday about 2:30 – 12 May – Lilian and I met him at Elmers End Station. There he was tall and smiling. A happy meeting. He was in battle dress with a Kitbag under his arm, thin and tanned. We had lunch and got out for the table some of the things we have been saving up just for this occasion. But his appetite is not great, but it is growing. He needs building up. His spirits are rising and he has improved much during the month. He was due to go to Canada after a fortnight with me, but I went to RCAF HQ and succeeded in having him taken off the draft, so now he is back with us again. It is happy days with him and he seems much more content than Eric, satisfied to rest and be at home. He looks well and fit, but one day in the garden he tried to dig and he clearly had no strength for it. He gave it up right away. He is allowed double rations for six weeks. His suits had been cleaned and pressed and were ready for him. We talk of the future, he will be a farmer, I think. I am glad of that.

Today he was going to see Mrs. Picken at Rachford, Essex. First he wanted to do a little sewing job and somehow he sat on the needle and it disappeared in his bottom. He was at the hospital in Beckenham this morning for an xray and tomorrow they will remove it. Poor Frank, it is a tragic-comic incident. He says he will have a wife to do his sewing. One day he went up to M.I. at Canadian Military HQ to see if there was a chance of Eric coming on leave, and it seems that they are trying to get him over. It will be nice to have the two of them with me for a little while. GC is very fond of Frank, and he enjoys her company. It is days of harmony and soothing joy, oneness of purpose. I am glad to think of the good influence he will be when he gets home. He is the same good boy as when he went away. GC observes that prison camp has not coarsened him a bit.

Frank has been telling us of life in Luft III at Sagan. The monotony could only be broken by the fun and excitement they could provide themselves. Betting about the war and many other things was one way. He holds now a cheque for £15 for which there is N.F.S. One fellow had a special way of betting. A Fl.Lt. Walton or Watson from Vancouver took him on. The I.O.U. was for one posterior osculation. He lost and the fellows made him redeem it!

Diary Entry

June 6, 1945

Min wrote after closing with X’s “Dennis gave me two last night for Mother’s Day, Wilf went one better, Bennie did say good night for a change.” How pathetic that she should record this. How mean and stupid they to withhold their affection thus. It will be different when Frank gets back. He will shame them and he will bring happiness and harmony to the house.

I went to see him last night on my way home. The needle was extracted and he was just waking up from the operation, looking awful in the face and eyes, but he smiled and joked, nevertheless. He said he knew he had used some terrible Kriegie language during the operation. I only stayed for a couple of minutes, for it was outside visiting hours and he was too dazed.

Diary Entry

June 7, 1945

Called on Frank on my way home. He looked himself again and very happy. Coming from the operation in his delirium he was laughing when JU52s went down and he was crying when he thought he was going to “Kriegie Camp” again. Clearly the moments of his combat and his crash landing in the Spitfire are impressed on his mind. An Irishman in a bed opposite said he had called Hitler and Himmler for “Irish Sons of Bitches!” The operation took ¾ hour, though they pretend it was only a matter of a few minutes and his scar is about 4 – 5 inches long.

Diary Entry

June 18, 1945

Saw Frank off on the 12:30 Saturday for Bournemouth. The queue must have run into thousands and he first train could not take him. Next was an hour late but I did not wait for it. We shall miss him.

Diary Entry

June 25, 1945

Frank gave me a ring. He is still at Bournemouth and can’t get leave. He is having pleasant weather and is enjoying his stay there.

Diary Entry

June 30, 1945

Had a letter yesterday from Frank. He is leaving 3rd July – that will be Tuesday.

If you wish to contact us, please leave a comment or fill out this form below.

Intermission – Flight Lieutenant Robert Marshall Buckham

More about Flight Lieutenant Robert Marshall Buckham by Pierre Lagacé

Flight Lieutenant Robert Buckham is seen on the left with Frank Sorensen. This photo is part of Flight Lieutenant Frank Sorensen courtesy of Vicki Sorensen.

I had not idea who was Flight Lieutenant Robert Buckham before Vicki told me I had forgotten to add this photo on Sunday’s post.

I am glad she did. Flight Lieutenant

Robert Buckham’s name is featured on several websites.

https://legionmagazine.com/en/1999/01/robert-buckham/

Excerpt

Art was Robert Buckham’s life—or at least his sanity. It got him through the hell of two forced marches during his time as a PoW in Germany during WW II. From top to bottom: On The March, April 1945; RAF Polish Officer.

Born in Toronto in 1918, Robert Buckham didn’t go overseas as a WW II artist. He went over as a pilot with the Royal Canadian Air Force and ended up flying Wellington bombers over France and Germany. He was with 428 Squadron when his plane was shot down over Bochum, Germany, on April 8, 1943. The pilot and crew survived the crash, but were captured by the Germans and imprisoned at Stalag Luft III, 120 kilometres northeast of Dresden. It was from there that the Great Escape took place on March 24, 1944.

On Christmas Day 1944—a small, green hardboard book was issued to the airman. It contained 115 blank pages which Buckham began to fill with notes and sketches prior to the first of two forced marches the PoWs endured. The book, which fit nicely into the large pocket on Buckham’s tunic, formed the basis of an illustrative diary called Forced March to Freedom.

Excerpt

“Endurance was our only resource.” (Diary entry of Robert Buckham, Feb. 2 1945.)

There isn’t much to celebrate in these troubled times, but May 8 marks the 75th anniversary of VE Day, Victory in Europe Day.

For one Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) pilot it was the end of a desperate and brutal march across Europe by thousands of Allied prisoners of war. Flight Lieutenant Robert Buckham’s illustrated diary would become a book, Forced March to Freedom (1984) and later a documentary film (2001).

The flyer was also one of the many young Canadians who helped in the most famous P.O.W. escape of the Second World War.

Most impressive are his paintings and drawings here…

Here an article in a magazine.

https://archive.macleans.ca/article/2003/1/13/a-brutal-march

Excerpt

A BRUTAL MARCH

History

Wartime diaries record a trek of 10,000 POWs

KEN MACQUEEN

THE DIARIES, naturally, look as though they survived a war. The paper has yellowed, the covers are sprung, the leaves are loosed by age and harsh circumstance. At 84, Robert Buckham, ex Flight-Lieut. RCAF, 428 Squadron, 6 Group, Bomber Command, sits in the dining room of his West Vancouver home leafing through a past potent with the dreams and visions of a life interrupted.

He was piloting his 10th mission over German occupied territory when guns downed his Wellington bomber on April 8, 1943. He and his entire crew were captured and imprisoned, the officers sent to Stalag Luft III, site of the Great Escape. “I said I was going to major in art there, and I did,” he says. Buckham, an artist and advertising art director before and after the war, put his talent to good use. He forged travel permits used during the mass escape of 76 fellow officers, and recorded in word and drawing the harsh existence of a prisoner of war.

The journals begin behind the wire of the infamous camp, but they also record a lesser known chapter of history. In the war’s dying months, a ragged column of 10,000 POWs were marched through an eastern and central European winter and springheld hostage by the desperate remnants of the German army. Buckham’s illustrated diary and his paintings—rolled in a carry cylinder of soldered powdered milk cansare among the only visual record of that brutal trek in which an unknown number of prisoners died. Some diary extracts:

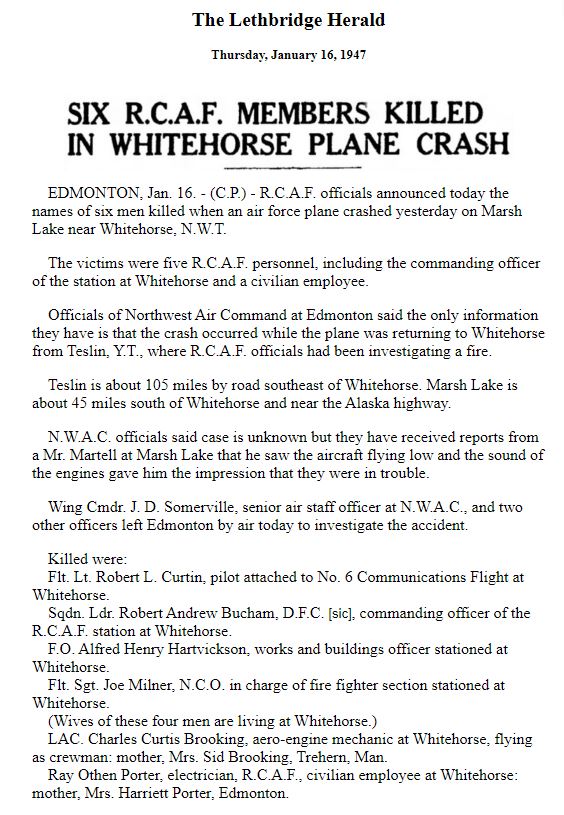

Robert Marshall Buckham is not to be confused with Robert Andrew Buckham who was also a RCAF pilot in WWII.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/122196702/robert-andrew-buckham

More about him (source airforce.ca)

BUCKHAM, F/L Robert Andrew (J15246) – Distinguished Flying Cross – No.416 Squadron – Award effective 25 May 1943 as per London Gazette dated 4 June 1943 and AFRO 1187/43 dated 25 June 1943.

Born in Golden, British Columbia, 5 October 1914. Educated at King Edward High School, Vancouver, 1928-1930, Prince of Wales School, Vancouver, 1930-1931, and Vancouver Technical School, 1931-1932 (mechanical engineering, drafting, engine drawing). Employed in “carriage work”, 1932-1935 and as driver and salesman, 1935 to 1939. Took flying lessons in Vancouver and logged 60 hours total, November 1939 to June 1940 (Luscombe and Fleet aircraft).

Enlisted in Vancouver, 23 October 1940 and posted to No.1 Manning Depot, Toronto. To No.1 WS, Montreal (non-flying duty), 15 November 1940 To No.1 ITS, Toronto, 8 February 1941; graduated and promoted LAC, 16 March 1941 but not struck off strength until 29 March 1941; reported next day to No.10 EFTS, Mount Hope; may have graduated 16 May 1941 but not taken on strength of No.2 SFTS, Uplands until 28 May 1941; graduated and promoted Sergeant, 8 August 1941). To “Y” Depot, 10 August 1941. To RAF Trainee Pool, 27 August 1941. To No.59 OTU, 29 September 1941; posted to No.416 Squadron (22 November 1941-1 July 1943).

Promoted Flight Sergeant, 1 March 1942. Commissioned 8 March 1942 (Appointments, Promotions, Retirements dated 1 April 1942). Promoted Flying Officer and Acting Flight Lieutenant, 18 December 1942. Attached to Central Gunnery School, Sutton Bridge as instructor, 2 June to 30 June 1943 or 1 July to 1 August 1943, when posted to Station Digby to instruct in gunnery.

Confirmed as Flight Lieutenant, 3 June 1943. To No.421 Squadron, 13 September 1943; promoted Acting Squadron Leader and posted to No.403 Squadron as Commanding Officer, 5 October 1943; attended Fighter Leader School, Milfield, 23 February to 1 March 1944. to No.127 Wing HQ, 13 June 1944. Promoted Acting Wing Commander, 14 June 1944.

Repatriated to Canada, 7 August 1944. To War Staff College, 10 September 1944. To Station Patricia Bay, 19 November 1944. To Canadian Joint Staff, Washington, 8 May 1945 for American staff course. To No.6 Release Centre, Regina, 7 August 1945 to command. Retained in service and posted on 1 November 1945 to No.2 Air Command, Winnipeg. To Northwest Air Command, Edmonton, 16 December 1945 (staff duties). To Station Grande Prairie, 21 December 1945. To Northwest Air Command Headquarters, Edmonton, again as of 29 December 1945. To Station Watson Lake, 27 January 1946. To Station Whitehorse, 25 February 1946. Confirmed as a Permanent Force member of the RCAF, 1 October 1946 with rank of Squadron Leader.

Killed in flying accident, Whitehorse, 15 January 1947 (passenger aboard Expeditor 1394, pilot F/L R.L. Curtin; en route Whitehorse to Teslin; accident report on National Archives of Canada microfilm T-12342; aircraft had run into a snowstorm and made an error in selecting fuel switches; Pilot appears to have attempted to land with wheels up but aircraft exploded on striking ground; five servicemen and one civilian killed).

Credited with the following victories:

19 August 1942, one FW.190 destroyed and one Ju.88 damaged; 3 February 1943, one FW.190 destroyed; 3 April 1943, one FW.190 destroyed (shared with another pilot); 3 May 1943, one FW.190 destroyed; 14 May 1943, one FW.190 destroyed; 16 May 1943, one FW.190 damaged; 19 September 1943, one Bf.109 destroyed; 24 September 1943, one FW.190 destroyed and one FW.190 damaged. See Chris Shores, Aces High.

DFC presented a Buckingham Palace, 9 November 1943; invested with Bar by Governor General, 10 December 1947. The subject of a portrait by artist Edwin Holgate (Canadian War Museum collection). See RCAF photo PL-19870 (ex UK-5440 dated 7 October 1943, outside tent in England); PL-19877 shows F/L R.A. Buckham and F/L Dean Dover, 24 September 1943 (Dover shining shoes after losing a coin toss); PL-22164 shows him with Buck McNair; PL-22285 shows Buck McNair, R.A. Buckham and Hugh Godefroy, 12 November 1943. RCAF photo PL-28554 (ex UK-8460 dated 8 March 1944) shows him in his Spitfire. Photo PL-28556 shows Buckham leaning on Spitfire wing. //

This officer has taken part in a large number of sorties and has proved himself to be a fine fighter and a first class leader. He has destroyed four enemy aircraft and damaged five locomotives. //

BUCKHAM, F/L Robert Andrew, DFC (J15246) – Distinguished Flying Cross (United States) – No.416 Squadron – Award effective 17 July 1943 as per London Gazette dated 20 July 1943 and AFRO 644/44 dated 24 March 1944. Public Records Office Air 2/ 9599 has USAAF 8th Air Force General Order No.104 dated 16 July 1943 which gives citation. // For extraordinary achievement while escorting bombers of the United States Army Air Force on seven bombing raids over enemy occupied Europe. Flight Lieutenant Buckham has fervently sought out the enemy on each occasion and has destroyed three enemy airplanes in aerial combat. The courage and skilful airmanship displayed by Flight Lieutenant Buckham on all these occasions reflect great credit upon himself and the Armed Forces of His Majesty’s government. //

BUCKHAM, S/L Robert Andrew, DFC (J15246) – Bar to Distinguished Flying Cross – No.403 Squadron – Award effective 8 August 1944 as per London Gazette dated 11 August 1944 and AFRO 2101/44 dated 29 September 1944. //

During May 1943, this officer was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. Since then he has flown on a great number of sorties and on many occasions has successfully led his wing, sometimes under very adverse weather conditions. He is a fearless leader and set an inspiring example to those serving under him. //

NOTE: Public Record Office Air 2/9633 has recommendation drafted about 28 March 1944 when he had flown 167 sorties (327 operational hours), of which 83 sorties (141 hours) had been since his previous award. The text is more detailed than that published. // Since the citation for the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross to this officer on May 24th, 1943, he has flown a further 142 hours on operations involving 83 offensive sorties. The types of operations comprise Ramrods, Rodeos, Circus’ and Rangers. He has destroyed a further two aircraft and damaged one bringing his total personal score to 6 ½ destroyed, two probable and two damaged. //

He is an outstanding fighter leader who is an inspiration to those serving under him. Absolutely fearless personally, he combines this quality with innate good judgement in the air. He has led the Wing on many occasions, always successfully and sometimes under very adverse weather conditions. //

This was favourably endorsed by his Wing Commander (Flying) on 30 March 1944, by an Air Vice-Marshal (appointment not stated) on 11 April 1944, by the Air Officer Commanding, 2nd Tactical Air Force (Air Marshal Coningham) on 24 April 1944, and by the Air Commander-in-Chief, Allied Expeditionary Air Force (Air Chief Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory) on 28 May 1944. //

Assessments: “A very fine flight commander who should go a long way.” (S/L F.A. Boulton, 15 January 1943) //

“A very satisfactory officer and squadron commander.” (W/C M. Brown, 25 October 1943). //

“It is felt this officer could fill a staff appointment at the level of his present rank. He would probably make a successful commanding officer.” (G/C R.M. McKay, 17 November 1944, on completion of War Staff course). //

“Has commanded No.6 Release Centre. Somewhat lacking in administrative experience. Better employed at a flying unit. A very good type of young officer. Retention in service recommended. With more administrative knowledge and experience this officer should have no difficulty in making a career in the RCAF.” (A/V/M K.M. Guthrie, No.2 Air Command, 30 November 1945). //

Other Notes: Damaged Spitfire P7673, Peterhead, 18 December 1941. Non-operational flight. He wrote, “On landing machine commenced to swerve to starboard. Left rudder was applied fully and brake was tried. The brakes did not hold and the aircraft slipped off the runway into the mus and turned on its nose.” Squadron Leader P.P. Webb concluded, “Pilot was inexperienced on Spitfires and did not counteract the swing of the aircraft on its initial stage.” //

Damaged Spitfire R7224 at Dyce on 3 June 1942, non-operational flight (ferrying aircraft from Peterhead). At the time he had 325 hours on all types, 126 hours on Spitfires. He reported, “At 1545 hours on June 3rd I was landing Spitfire aircraft R7224 at Dyce aerodrome. On touching down, the port oleo sheared off, due to the drift of the aircraft. I took off again, retracted the other leg and made a belly landing on the grass.” Although there was a crosswind affecting the landing (and S/L P.L.I. Archer seemed forgiving), the Wing Commander concluded, “Accident due to error of judgement. P/O Buckham is being given some dual in the Master on cross wind landings.” //

Spitfire EP114 damaged on 26 January 1943 during operational sortie (Escort, Circus 256), category AC (repair by contractor’s working party). No details. //

On 12 July 1944 he filled a form in anticipation of repatriation stating he had flown two tours, 250 sorties and 500 operational hours (last sortie on 1 July 1944). He gave his total overseas flying as 810 hours, comprised of 30 hours on Hurricanes (at OTU), 20 hours on Masters, ten hours on Magister and 750 hours on Spitfires.. //

His file includes an application for Operational Wings dated 15 November 1945. It includes a sortie list which is obviously incomplete as it does not begin until 7 September 1943. Transcribed for the historical record. Some dates clipped off, hence (?): //

7 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod (1.30) //

8 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod (1.30) //

8 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod (1.30) //

9 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Starky (1.30) //

9 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Starkey (1.15) //

9 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Starky (.30) //

11 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 216 (1.50, Beamont-le-Roger) //

13 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Rodeo 251 (1.10, Ambleteuse) //

18 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 228 (1.40, Beauvais) //

18 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 230 (1.40, Beamont-le-Roger) //

19 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 233 (1.50, Lans) //

21 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 235 (1.30) //

22 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 237 (1.45, Evreux) //

23 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 239 (1.40, Conches) //

23 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 240 (1.40, Beauvais) //

24 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 242 (1.45, Evreux) //

24 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 243 (1.30, Beauvais-Tille) //

25 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 246 (1.10, St.Omer) //

26 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 248 (1.40, Beauvais) //

27 September 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 252 (1.40, Rouen) //

2 October 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 255 (1.45, Woensbrecht) //

3 October 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 257 (2.00, Woensbrecht) //

4 October 1943 – No.421 Squadron – Ramrod 258 (1.40) //

5 October 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 261 (1.35) //

15 October 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Rodeo 260 (1.45, Flushing area) //

18 October 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 272 (1.45) //

18 October 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 273 (1.40) //

18 October 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 274 (1.35, St. Omer) //

20 October 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Rodeo 263 (1.25) //

20 October 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 277 (1.25, Douai) //

22 October 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Rodeo 280 (1.40) //

24 October 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 283 (1.20, Amiens) //

24 October 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Fighter Sweep (1.30, Holland area) //

4 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Rodeo (1.25, Lille) //

5 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 291A (1.35) //

7 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 197 (1.30, Berck-Rouen area) //

7 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Circus 315 II (1.40, Doullens-St. Omer) //

8 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 300 (1.35) //

10 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 307 (1.50, Lille-Vendrevillers) //

10 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 308 (1.40) //

11 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 311 (1.45, Cherbourg area) //

11 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Fighter Sweep (1.35, Martinvash-Cherbourg) //

18 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Fighter Sweep (1.30, St.Omer-Hrdelot) //

19 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 325 (1.35, St.Omer-Bethune) //

25 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 330 (1.45, Cambrai) //

25 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 333 (1.40, Cambrai) //

26 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 335 (2.00, Fortress escort) //

26 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 336 (1.40, Amiens) //

30 November 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 341 (1.55, Fortress escort) //

1 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 343 (1.50, Cambrai) //

1 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 344 (2.00, Knocke-Rotterdam) //

4 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 349 (1.40, bomber high cover) //

5 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 351 (1.40, fighter umbrella) //

20 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 376 (1.50, rocket target) //

20 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 377 (1.40, rocket target) //

21 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 382 (2.00, Paris area) //

22 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 385 (1.45, Amiens) //

23 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Fighter Sweep (1.55, Nieuport area) //

24 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 392 (1.50) //

30 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod (2.00, Fortress escort) //

31 December 1943 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 403 (1.45, Cambrai area) //

4 January 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 425 (1.45, rocket target) //

5 January 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 426 (1.50, rocket target) //

8 January 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 427 (2.00, Cherbourg) //

23 January 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 472 (1.50, Lille area) //

24 January 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 475 (1.45, Dieppe) //

? January 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 476 (1.50, Brussels) //

? January 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 479 (1.35, St.Omer) //

30 January 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 499 (2.00, Cambrai) //

21 February 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod (2.00) //

22 February 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod (2.00) //

2 March 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod (2.00) //

3 March 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 616 (2.25, Laon area) //

3 March 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Fighter Sweep (1.20, Lille area) //

4 March 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Fort escort (1.40, from Brussels) //

6 March 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 640 (1.55) //

7 March 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod (2.15) //

8 March 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 637 (2.00) //

8 March 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ranger (1.45, Evreux and Paris) //

16 March 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Rodeo (1.50) //

20 March 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Rodeo (2.10) //

23 March 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod (2.10) //

10 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 713 (1.50) //

19 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 7.50 (1.30, bombing Noball target) //

20 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 757 (1.20, Noball target) //

22 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod (1.05, dive bombing) //

22 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 769 (1,20, dive bombing) //

23 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 777 (1.25, Noball target) //

23 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 779 (1.15, Noball target) //

26 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 795 (2.10) //

26 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 798 (1.55) //

27 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 800 (1,45) //

27 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 801 (1.20) //

27 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 803 (1.20) //

28 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod (1.05, dive bombing) //

29 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 806 (1.10, Noball target) //

30 April 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 811 (1.20, Noball target) //

7 May 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 839 (2.25) //

7 May 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 843 (1.20, Noball target) //

8 May 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 844 (2.30) //

8 May 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 848 (2.00) //

10 May 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 859 (1.55) //

10 May 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 863 (1.10) //

11 May 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 867 (1.25) //

13 May 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 881 (1.30, RR junction, Bourgourgeville) //

13 May 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 883 (1.25, rocket target, Fruges) //

30 May 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 946 (1.25, strafing Noball target) //

31 May 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 953 (1.00, Dieppe) //

3 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Ramrod 962 (1.20, strafing transport) //

6 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (2.00) //

6 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (2.00) //

6 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (2.00) //

6 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (2.00) //

7 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (2.10) //

7 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (1.55) //

8 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (1.55) //

8 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (1.55) //

10 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (2.00) //

10 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (2.00) //

10 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (1.55) //

10 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (1.55) //

? June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (2.00) //

12 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (1.55) //

14 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Fighter Sweep (1.45, Paris area) //

14 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Wing Fighter Sweep (1.55, Evreux and Lehavre) //

15 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (2.00) //

16 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Covering British cruiser (1.50) //

16 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Fighter Sweep (.45, near Caen) //

17 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Fighter Sweep (1.00, Caen and Falaise) //

18 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Bomb line patrol (1.30, Caen area) //

19 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Bomb line patrol (1.35, Caen and Falaise) //

22 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Invasion Beach Patrol (1.05) //

22 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Dive bombing (1.00, Bretteville ammo dump) //

23 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Armed reconnaissance (1.25, Lisieux area) //

23 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Dive bombing (1.30, Cheux) //

25 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Armed reconnaissance (2.30, Chartres) //

26 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Beachead patrol (1.20) //

26 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Beachhead patrol (1.05) //

28 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Bomb line patrol (1.45, Caen, Falaise) //

29 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Bomb line patrol (1.25, eastern flank) //

30 June 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Bomb line patrol (1.30, Bernay to Caen) //

1 July 1944 – No.403 Squadron – Bomb line patrol (1.25, Caen-Bermay- to Argentan).

Chapter Thirty-Two – December 1943 – Stalag Luft III, Sagan, Germany

Foreword written by Vicki Sorensen

My father, Frank Sorensen, immigrated to Canada from Roskilde, Denmark with his family in August 1939. He volunteered in the Royal Canadian Air Force in March 1941 and trained to become a Spitfire fighter pilot. He was shot down while serving with RAF 232 Squadron, over Tunisia, in North Africa on April 11, 1943 and became a prisoner of war at Stalag Luft III. He was an active participant in the tunnel digging operations that was later known as The Great Escape.

After my father’s death February 5th, 2010, when he was 87, I came into possession of letters written by him to his parents during the war that they had saved and given back to him. Along with the letters were numerous photos and service record documents. There were 174 letters in total which start from C.O.T.C., 1940, #1 Manning Depot, #3 Initial Flying Training School, #2 Elementary Flying Training School, #11 Service Flying Training School; all in Canada in 1941 to #17 A.F.U. (Advanced Flying Unit) and #53 O.T.U. (Operational Training Unit) in England in 1942. Then, his service from 1942 in RCAF 403 Squadron, in England, transferring to RAF 232 Squadron in Scotland, then to North Africa. Numerous letters are from 1943 and 1944 from Stalag Luft III, and then a handful from 1945. There were only two short letters from the long march from Sagan to Lubeck – one in March letting his parents know he was still all right, and one in May when they had just been liberated.

December 12, 1943

Stalag Luft III, Sagan, Germany

Dear Mother & Dad & Company;

Have just returned from a comedy “Twinkle, Twinkle Mr. Starr”, written by one of the Kriegies here. Though a Kriegy’s sense of judgement so far as theatrical shows go, is out of all proportions, I must admit I enjoyed it. It’s surprising to see the results of an effeminate looking — a few words censored with black marker — woman’s wig and make up. I don’t think I told you much of our daily lives here. I did mention the fact that we are six to a room, which serves as bed, living and dining room. We usually get up around 9:30 for breakfast: two slices of rye bread and Red Cross jam and coffee. If we get up early enough, the “stooge” has time to wash up before morning parade. During parade I have a chat with Boge (see note) from Copenhagen. He is in the Norwegian Air Force. After parade he and I walk once or twice round the camp. Returning to my room I always find it crowded with visitors, mostly Canadians, everyone doing his bit to fill the room, which is just large enough for three double bunks, six stools and one table, with cigarette smoke so I either go visiting other rooms or have another walk before lunch. Lunch: one slice of rye bread and Red Cross cheese, biscuit and coffee, sometimes we get a bowl of soup. The afternoons I find quiet enough for studying, when it gets crowded I play chess, read a book or go for a walk, or if I happen to be “browned” off, which I am more often than not, I simply get up on my bunk, draw a blanket over me and let my thoughts wander back over the past. Supper is the meal of the day: Spam or Red Cross bully beef, potatoes and turnips and a pudding of Red Cross biscuit and raisins and a cup of Red Cross cocoa. In the evening I write letters or just sit around being too tired to study. I often take the mandolin and a stool to the wash room and kill an hour or two. Go to bed at midnight. Must have been Wilfred’s birthday yesterday. Haven’t had much mail recently. Send more snaps.

Love to all, Frank

December 22, 1943

Stalag Luft III, Sagan, Germany

Dear Mother & Dad & Company;

Today I have Dad’s letter of November 19, 1943 and two from Jean, the first mail this month. Pleased to hear about Ben’s achievements. Would like a personal account from them all of this past summer. Jean wrote me a nice letter October 21, 1943. Here everybody is getting ready for Christmas, the two main problems being food, “alky.” We have a bit of Argentine bulk and ¼ a N.Z. parcel per officer as extra Christmas food and instead of ordinary English parcels we get a Christmas parcel for Christmas week. Several months ago people began putting down barrels of brew made from Red Cross raisins and sugar, this amounting to an average of a couple of pounds of each per officer, but as I don’t agree with such a waste of food I refused to join in on the room brew. — two lines censored with black marker — I’ve made it a habit of mine to walk at least 10 km a day, yesterday I did 16 km. — two lines censored with black marker — Had a book from Denmark. The Worlds Most Northern Doctor, about a Danish doctor in Greenland. Don’t know who sent it. Am reading “Rebecca” at present. Very good.

Love to all, Frank

December 29, 1943

Stalag Luft III, Sagan, Germany

Dear Mother & Dad & Company;

Just discovered that I still haven’t written my three letters this month and as mail for December is collected tomorrow I’ll try to fill out these blank lines before going to “bed.” My Christmas mail arrived yesterday. Five from Denmark. Haven’t heard from Mrs. Firdinansen yet I’m disappointed there. Christmas was awfully boring as I wasn’t drinking. Feeling sure this is the first and last Christmas here. Am looking forward to returning to your new home. It’s getting late now, must cut bread for tomorrow’s breakfast, as I’m “stooge;” will finish this off tomorrow.

We were a little late this morning and got up just in time for parade so we had “breakfast” after parade. If you did not get my diary from North Africa will you write my adjutant; I asked him a couple of weeks before I was shot down if he would keep it for me in case I failed to return someday and he said he would. I don’t suppose there were any pictures in my camera. Why don’t the kids write? Incoming mail is unlimited!!! It’s pretty dull here when months go by with no mail. So Jean also reads these, good show!

Love to all, Frank

Note

Source

http://www.danishww2pilots.dk/profiles.php?person=19

Sgt Arne Johnny Langhoff Bøge

(1917 – 1976)

Arne Johnny Langhof Bøge volunteers for the Royal Norwegian Air Force during the Second World War. He is shot down on a mission in August 1943 and becomes prisoner of war in Stalag Luft III.

Arne Johnny Langhof Bøge is born on 04 November 1917 in Copenhagen. During the Second World War, he volunteers for the Royal Norwegian Air Force and is trained at Flyvåpnenes Treningsleir (FTL) in ‘Little Norway’, Canada, from mid-1941.

He is trained as pilot and is posted at No. 332 (Norwegian) Squadron in June 1943. In the beginning of June 1943 he is admitted to the hospital for reasons that I have not been able to trace. We know this because Kjeld Rønhof and Carl Erik Randløv visits him at hospital.

He participates in his first operational sortie – a convoy patrol – on 26 June 1943 taking off at 1000 hrs. from North Weald in Spitfire Vb (BL294). According to production information on Spitfires this is a Spitfire IX, but it is listed as a Spitfire Vb in the 332 (N) Sqn operational record book.

The Last Mission

On 15 August 1943 the squadron is part of the escort of B-17 Fortresses heading for Amiens and Vitry (Ramrod 202). A J L Bøge takes off in Spitfire IX ( BR630 ‘AH-‘) at 1850 hrs. with the rest of the squadron. They meet three boxes of 20 B-17s each off Berck-sur-Mer in Northern France heading for the target. Having bombed the target, the B-17s set course for Gravelines.

No. 332 (N) Squadron sees 6 Fw 190s of I. and II./JG2 approaching the bombers from astern. The squadron dives towards the enemy aircraft and two pilots engage in combat near Vitry and between Arras and Donai. Lieutenant Werner Christie (Blue 1) and his wingman, A J L Bøge (Blue 2), both destroy a Fw. 190. Unfortunately Bøge is hit.

According to the 332 (N) Sqn. operational record book (appendix 20):

K. Rønhof states that he saw another Fw 190 firing on Sgt. A Bøge’s aircraft, hits being made all over the Spitfire IX. Sgt. A. Bøge then called up on his R/T stating that his aircraft was on fire. He was told to turn his aircraft south and go as far as possible and bale out. To this he answered “O.K. Cherio”. E. Westly states that when seing Sgt. A. Bøge’s aircraft last it was heading South towards a forest and it was followed by several (about 5) Fw 190’s.

A J L Bøge manages to bail out but is captured by the Germans and interned in Stalag Luft III. It was Bøge’s 7th operational sortie at the squadron.

After VE-day

Following the German surrender he returns to Denmark and is attached to the Danish Naval Air Service. He is promoted to Flyverløjtnant af 1ste Grad on 1 June 1946. He is transferred to the Royal Danish Air Force when it is established in 1950. On 1 March 1952 he is promoted to Kaptajn (Captain).

(Ancker, 2001; AIR 27/1728; Franks, 1998; Foreman, 2002)

If you wish to contact us, please leave a comment or fill out this form below.

Intermission – May 1943 – Letters from Frank’s father

Note from Vicki Sorensen

Marinus Sorensen, Frank’s father, wrote letters. It was after he had received a letter from the squadron leader A.L. Winskill after his son Frank was shot down.

Saturday, May 1, 1943

This morning I have a letter from his Squadron Leader. It is dated 22nd April and it reads:

“Dear Mr. Sorensen:

Before you receive this letter you will have been informed by the Air Ministry of the fact that your son, No. J15811, P/O C.F. Sorensen, is missing from operations.

Unfortunately, at present I am unable to give you any definite information but it would be unfair to raise any false hopes as to his being alive and, while there is no definite proof of his death, the circumstances in which he failed to return from operations, I regret to say, are such that there is virtually very little hope of his being alive.

At the time your son was reported missing we were in contact with the enemy, fighting was taking place everywhere and nobody saw exactly what happened to him. As soon as any further information is received, I will see that you are immediately advised.

May I now express the great sympathy which I, and all his friends and colleagues in the Squadron feel with you in your anxiety.

All his personal effects will be taken care of by the Standing Committee of Adjustment who will get in touch with you, and if there is anything I can do or any further information which you would like to hear, please write me and I shall be glad to help you all I can.

A.L. Winskill

Squadron Leader, Commanding

No. 232 Squadron”

I shall of course write to him and thank him for his letter. When I hear about Frank’s personal effects I shall ask to have them sent on to Kingston, for I am crowded as it is and if I receive them here I might not be allowed to send them out of the country, at least not before the war is over.

I see Frank everywhere. There is a young pilot of Frank’s stature crossing the square. I must wait and see him turn around to get his profile. He looks so tall and smart, just like Frank, so smart in his new officer’s uniform. Here comes a young sergeant lugging along with his kitbags and packs as I saw Frank coming and going on his leaves.

I see so many things on the square. Here comes a little boy along with his Daddy, hand in hand, chatting and enquiring about the things about him. He is about the size of Frank when he and Eric unfailingly saw me off and met me at the station in Glostrup, as did you and Bennie and Wilfred in Roskilde. And I pass a young mother with her baby in a pram, a nice round baby face and fat little hands. Yes, there was a time, when Frank was a baby. There was a time, too, when death was near, when your mother could not sleep for fear. But one morning a little hand grasped a tiny toy elephant, his eyes could see us again and he recovered and could smile anew. From the first he was your defender, whenever we pretended that it was all wrong about you being a girl, and though you were so much younger, yet I know, that the young girls he met were criticized to your standard. How much more could a brother admire a sister?

I have always been so grateful that we moved when we did, that things shaped themselves so that we could get away. But now I ask myself would Frank have been spared had we stayed? What a gracious thing it is that we cannot know. We have been spared and Frank had to be the prize, the sacrifice. He went to this task eager and happy, he felt the grave responsibility of it and he shirked it not, but he longed to get it over and he longed to get back to you all again, to his home, and to fit himself for a career after the war.

Sunday May 2, 1943

It is so nice to get around to Sunday when my Good Companion is with me all the day. She should have been over with her father and sister Min today, but I don’t think she likes to leave me more than necessary to brood alone over Frank. I was lucky to get kippers yesterday. We have not had that for many a month. Perhaps mother will say that you have not had it for years. And I got a mackerel too and that is going to be our dinner. Miss Hall is in my room preparing it and I am in her room writing. It is a dull day and cold and I have the geosphere lit to temper the room. I listen in to all the news bulletins eagerly for news of safe arrival of a fresh Canadian contingent, which may carry Eric. I wish he was not coming, but I long to have him here just the same. He has had a hard spell of training and I fear he has a hard time ahead of him. Pray God that he may be spared for us, that he may see the time when men shall “beat their swords into ploughshares and their spears into pruning hooks: nation shall not lift up a sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore.” May it be Dennis’s, Bennie’s and Wilfred’s lot not to have to learn war. I believe in this better New Order that is coming, it will be your inheritance, but I hope that my eyes shall see the beginning of it, for it will, naturally take time to unfold itself, it cannot come about night over. I try to anticipate where we shall be when the war is over – Canada or Denmark, but I fear that Russia is complicating matters so much. They are helping to overcome Germany now, but what then? Since we are not prepared to accept their way of life, will they accept ours? I think we will probably come into a period of armistice, not real peace and then there will be a final war with Russia, a war not of our seeking or planning, a war, which will be an even greater surprise for us, a war, which will be settled in the Holy Land. So it may be a good while before real peace comes, and even with peace, who says that we can just go back to the old stands and carry on?

I suppose that I should be very grateful that I can carry on here in the mean time, but when I remember the ease and the lack of thought and consideration for others, with which I was repeatedly exposed to the dangers of the Atlantic and other journeys, then I am afraid that I am embittered and hardened a bit, knowing that it was only their own convenience that was considered. Their minds were servile to a senior whom they were not prepared to argue with and reason with, I mean the Vice President, Mr. Stephen (of the CPR that is).

And now I know that you will all strive to be a comfort to mother and to ease her day and I hope too, that the grief, which is in all hearts, will compel us to sweeten the day and the task for each other, make love and tolerance and understanding grow, such as Frank would rejoice to see it. There are good fights for us to fight, with ourselves and in our home. Frank fought his good fight and fought it well. Perhaps he is carrying on the fight right now, flying with Michael, his Patron! One day Michael and his host will overcome our enemies for us.

Now I will close, Miss Hall sends her love and deepest sympathy to you all, for she loved him too. And love and thoughts and longings from Dad.

More on the Squadron Leader A.L. Winskill

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Archibald_Winskill

https://www.rafweb.org/Biographies/Winskill_AL.htm

http://www.bbm.org.uk/airmen/as-winskill.htm

Archie Little Winskill was born in Penrith, Cumberland on 24th January 1917 and educated at Penrith and Carlisle Grammar Schools. He joined the RAFVR in April 1937 as an Airman u/t Pilot and was called to full-time service at the outbreak of war.

From September 1939 to June 1940 Winskill was a staff pilot at B&GS Catfoss. Commissioned in August, he arrived at 7 OTU Hawarden on the 25th and after converting to Spitfires joined 54 Squadron at Catterick on 16th September 1940.

He was posted to 72 Squadron at Biggin Hill on 3rd October, moving to 603 Squadron at Hornchurch on the 17th. Winskill claimed a Me109 probably destroyed on the 28th, shared a He111 on 21st November and destroyed two CR42’s on the 23rd.

On 6th January 1941 Winskill was posted to 41 Squadron at Hornchurch and later became a Flight Commander. He destroyed a Me109 on 14th August but on the same day he was shot down near Calais in Spitfire Vb W3447.

He baled out and a French farmer immediately hid him in a cornfield until nightfall. The farmer’s son then took him to the farmhouse where he was fed.

Winskill spent the next few days in a barn, where the farmer’s son visited him with food each day. After two weeks in a safe house Winskill, dressed as a farmworker, was passed to various houses by bicycle before being put on a train for Paris. Due to the necessary secrecy he was not aware that he was being passed down the ‘Pat O’Leary’ Line, one of the most successful escape lines through occupied France. Two other evaders had joined him and they were taken first to Marseille and then to Aix-le-Therme at the foot of the Pyrenees.

On the night of 3rd October they were passed to an Andorran guide who took them over the mountains. After an arduous night-climb they managed to reach Andorra before travelling to Barcelona where the British Consul-General arranged to send them to Gibraltar via Madrid. Three months after being shot down, Winskill arrived back in England.

Fifty-seven years later, Winskill returned to France to meet Felix Caron, the boy who had helped him to escape, the Frenchman still had Winskill’s flying helmet, discarded by him as he hid in the cornfield.

Winskill was awarded the DFC (gazetted 6th January 1942), being then credited with at least three enemy aircraft destroyed.

No longer allowed to fly over France, because of his knowledge of French escape routes, Winskill formed 165 Squadron at Ayr on 6th April 1942 and commanded it until August. He then took command of 222 Squadron at Drem until September, when he became CO of 232 Squadron at Turnhouse. Winskill took the squadron to North Africa in November.

On a sweep over the Mateur area on 18th January 1943, he was shot down, probably by Fw190’s, after ditching in the sea he swam ashore.

Winskill destroyed a Ju87 and shared another on 7th April, damaged a Fw190 on the 27th, destroyed a Ju88 and a Me109 on the ground at La Sebala airfield on 7th May and damaged a Me323 on the ground on the 8th.

With his tour completed, Winskill was awarded a Bar to the DFC (gazetted 27th July 1943) and returned to the UK.

He commanded CGS Catfoss from September 1943 to December 1944. He then went to the Army Staff College, Camberley for a course, after which he was posted to a staff job at the Air Ministry in June 1945.

He was in Japan in 1947, commanding 17 Squadron, serving with the Occupation Forces.

Winskill was made a CBE (gazetted 11th June 1960) and in 1963 he became Air Attache in Paris. He retired from the RAF on 18th December 1968 as an Air Commodore.

He was Captain of the Queen’s Flight from 1968 to 1972 and was created a KCVO in 1980 (CVO 1973).

In 1972 Winskill arranged for the body of the Duke of Windsor to be flown from France to Benson in Oxfordshire, where it lay in state in the station’s church.

He died on 9th August 2005.

Intermission – Friday, April 30, 1943 – Dearest Eileen

Note from Vicki Sorensen

Marinus Sorensen, Frank’s father, wrote a letter to his daughter Eileen. It was after her brother Frank was shot down.

London, England

Friday, April 30, 1943

Dearest Eileen;

I have still your letter of the 26th February – a nice letter – to reply to and to thank you for. It gives me great joy to have your letters and to see how much better you can write as time goes on.

Just over a fortnight ago I had the terrible news about Frank, nothing except confirmation of his being missing has come through since then. Yesterday I had mother’s air graph written on the 19th, which was the same day I wrote to her and sent it by airmail, so I imagine that you must have this letter now. I was so sorry to hear about Preben too. Mother’s stay with the Gustavsen’s can not have been a very happy one, but perhaps they could be a comfort to one another. I will be glad to see Eric when he comes, but I would rather that he had stayed with you. I am now expecting to have a wire from him any day to say that he has landed.

But with Frank in mind we have not had a happy day since we had the news, for Miss Hall has also felt it keenly. There are so many little things to remind us about him. The other night I found her in trouble, she had been looking over his snapshots. But who would not grieve, who knew him? Today there was a letter from him dated 26, 27 and 28th March. Soon the last letter will come. Just as I do not want to hear the record of his speech, so I do not like these post letters.

Do you remember that one of his mates in one of the camps in Canada smashed his mandolin? He must have thought of the happy hours it had given him in Denmark and in Canada, too, for he carried the broken keyboard along with him over here. It could be of no value, except for the memories. Do you remember in Roskilde how he would sing up and play too, when he was studying and had solved a problem! What a happy thing it was, that mother should understand his need well enough to buy the first banjo for him. When was money better spent? And now the broken mandolin neck is symbolical of himself, of his own broken life, and it hangs on my wall with his picture in a ribbon that was also a keepsake of his, a ribbon with the lettering: HMS COURAGEOUS.

More letters to Eileen tomorrow…

Intermission – Rear Gunner Flight Sergeant Nicholas S. Alkemade, 115 Squadron RAF — Aviation Trails

He was shot down on the same day of the Great Escape, and after he was sent to Luft Stalag III as a POW, the same camp as Frank Sorensen.

There have been many stories about bravery and acts of courage in all the Armed Forces involved in war. Jumping out of a burning aircraft at 18,000 ft without a parachute must come as one of those that will live on in history. There have been a number of recorded incidents where this has occurred, […]

via Rear Gunner Flight Sergeant Nicholas S. Alkemade, 115 Squadron RAF — Aviation Trails

Intermission – Remembering William Thompson Lane

Contribution by Pierre Lagacé

This post was first published on another blog created to pay homage to all who served with RCAF 403 Squadron during WW II. In a sense this blog about Flight Lieutenant Sorensen owns a lot to Stephen Nickerson who had identified several of the pilots seen on the group picture. He was the one who had identified Vicki Sorensen’s father.

Original post

Last September Stephen Nickerson was remembering this pilot with a comment.

I have one story about William Lane. On March 13, 1943, the 403 led by S/L Ford was protecting the last box of 70 fortresses on a raid to Amiens. The American bomber commander decided to take (as Charles Magwood mentioned in his logbook) the group on a cook’s tour to Dieppe, Beauvais, Amiens and back to England. It was the job of the Canadian fighters to protect the American bombers but their fuel was running dangerously low on the outward leg. One pilot, P/O Cumming who was flying tail end Charlie in Magwood’s flight had to crash land in France due to lack of fuel. Ford’s Spitfire was having engine problems and he ordered the 403 to leave without him. P/O Lane flying in Red 4 or tail end Charlie in Ford’s flight stayed behind to protect his C.O. Ford and Lane were attacked several times by German FW 190s. Lane received damage to his plane while protecting Ford’s rear. Finally, Ford’s engine recovered and the two were able to escape. Lane’s actions had saved Ford from being shot down that day.

This is what I had written before about William Lane.

P/O William T. Lane

People in France remember Pilot Officer Lane.

Click here.

Le Spitfire est tombé dans le jardin de la ferme du château du Baron de BAULIEU à Baromesnil, abattu en combat aérien le 15 mai 1943 vers 17 heures, le numéro de série BR986, du squadron 403 (Royal Canadian Air Force). Son pilote le P/O WILLIAM T. Lane.

Une petite anecdote de la part de Mr Laurent VITON, la mascotte photographiée avec William T. Lane s’appelait Susan. Dans une interview du pilote, pour la Presse canadienne, il indiquait qu’elle appréciait le chewing-gum !

Translation

Spitfire serial number BR986 flown by P/O William T. Lane of RCAF 403 Squadron crashed in the garden of the farm of Baron de BAULIEU’s castle in Baromesnil after being shot down in a dogfight on May 15th 1943 around 5 p.m.

In an anecdote told by Mr. Laurent VITON, the mascot’s name photographed with William T. Lane was Susan. In an interview made with the Canadian Press, the pilot told that the dog liked chewing-gum!