Note

There are no letters in January 1944. The Great Escape occurred on March 24, 1944.

Foreword written by Vicki Sorensen

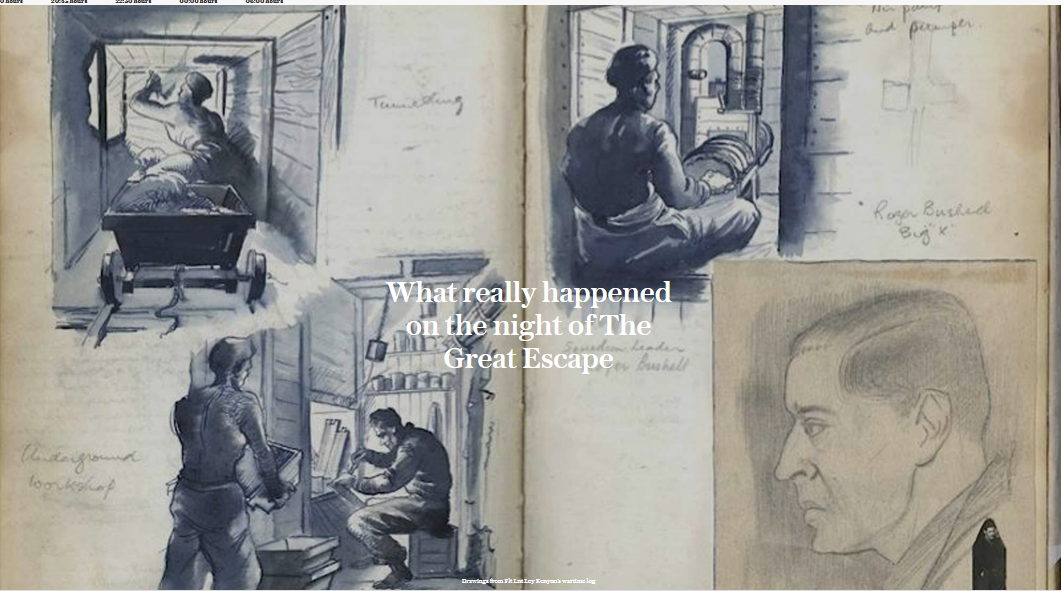

My father, Frank Sorensen, immigrated to Canada from Roskilde, Denmark with his family in August 1939. He volunteered in the Royal Canadian Air Force in March 1941 and trained to become a Spitfire fighter pilot. He was shot down while serving with RAF 232 Squadron, over Tunisia, in North Africa on April 11, 1943 and became a prisoner of war at Stalag Luft III. He was an active participant in the tunnel digging operations that was later known as The Great Escape.

After my father’s death February 5th, 2010, when he was 87, I came into possession of letters written by him to his parents during the war that they had saved and given back to him. Along with the letters were numerous photos and service record documents. There were 174 letters in total which start from C.O.T.C., 1940, #1 Manning Depot, #3 Initial Flying Training School, #2 Elementary Flying Training School, #11 Service Flying Training School; all in Canada in 1941 to #17 A.F.U. (Advanced Flying Unit) and #53 O.T.U. (Operational Training Unit) in England in 1942. Then, his service from 1942 in RCAF 403 Squadron, in England, transferring to RAF 232 Squadron in Scotland, then to North Africa. Numerous letters are from 1943 and 1944 from Stalag Luft III, and then a handful from 1945. There were only two short letters from the long march from Sagan to Lubeck – one in March letting his parents know he was still all right, and one in May when they had just been liberated.

February 9, 1944

Stalag Luft III, Sagan, Germany

Dear Mother & Dad, IE, brothers and Jean;

Mother’s dated November 1, 1943 and November 16, 1943 arrived today. I will repeat my request for at least four letters a month, two from Mother and two from the junior members of the family. One of my room mates here receives four from his Mother and four from his sister and when his father is travelling he also has four from him; besides the letters he gets from friends. Had five letters last month and they were all Danish. Mother’s reasons for only writing twice a month, or rather not letting the junior members fill in a couple of letters a month, are simply wrong, and I shall be very unhappy if I have no letters from the rest of the family. As for Eric, my best pal for 18 years, I regret having heard nothing from him, who knows, it might be the last chance of hearing from him at all. While we are at the mail situation, the most welcomed gift excepting the first couple of parcels from home, is an ordinary envelope of half a dozen snaps every month without a letter in it. Send old snaps if you can’t take new ones! Don’t let Red Cross talk you out of it, just send them. It took young Christensen 18 months to persuade his Mother to send him his first snaps. Have acknowledged four snaps without IE.

Love to all Frank

February 25, 1944

Stalag Luft III, Sagan, Germany

Dear Dad;

My second letter this month. Received three science books from Queen’s, but if I hope to do any studying in this room, I’ll have to introduce a quiet study period, which is going to be a little difficult, as certain members of the room enjoy filling the room with visitors any time of the day. Received my second parcel from Holmgren. One of the Canadians here, Foss Boulton (see note) expects to be repatriated in the near future. He suffers from loss of memory after a severe head operation. It has been very cold here lately, but we have always been able to keep the room comfortably warm. As I am very restless and being unable to keep my blankets on me at night, I sewed them into a sleeping bag. Ok now. I had a letter from Jean the other day, with a little picture of her. A lovely letter it was, as a matter of fact the first of its kind I have ever received from any girl. I used to read it every night before lights out and “throwing” quick glances at her picture, until a few days ago when I received a letter from Mother in which she mentions Jean’s apparent interest in my financial arrangements. Haven’t read her letter since. Oh well, back in the old mental treadmill again – most probably Jean is more interested in the R.C.A.F. officer and the 7.50 a day than the good-for-nothing student that I really am, but it was very soothing, while it lasted, to the nearly 12 month old Kriegy mind to try to believe that Jean really meant what she wrote in her last letter. Received 1000 cigs from Mrs. Spice. Though I still haven’t acquired the habit I’m glad to have them.

Love to all, Frank

March 20, 1944

Stalag Luft III, Sagan, Germany

Dear Mother & Dad;

Dad’s of December 24, 1943 and January 14, 1944 and Mother’s January 10, 1944 are the latest. The third parcel came from Gramp; everyone there ok. The winter has been dragging on for a long while now leaving the ground wet and miserable forcing most everyone to remain indoors and indoor life in a Kriegy camp does not make time go any faster. Just had a bite of Mother’s maple sugar, the cook, a new Squadron Leader in the room, had it out and was cutting some of it off for cooking with the bully and Spam to give a different taste to the meat. There is a fight every night between my better judgement and my stomach about that bully beef and spam. That it’s better than nothing is of course some consolation; but if anyone shows me bully beef or spam or a tin opener when I get home – I repeat what I have written before that I would rather have one snap than a dozen letters even old snaps, anything.

Love to all, Frank

If you wish to contact us, please leave a comment or fill out this form below.

About the escape

Source Wikipedia

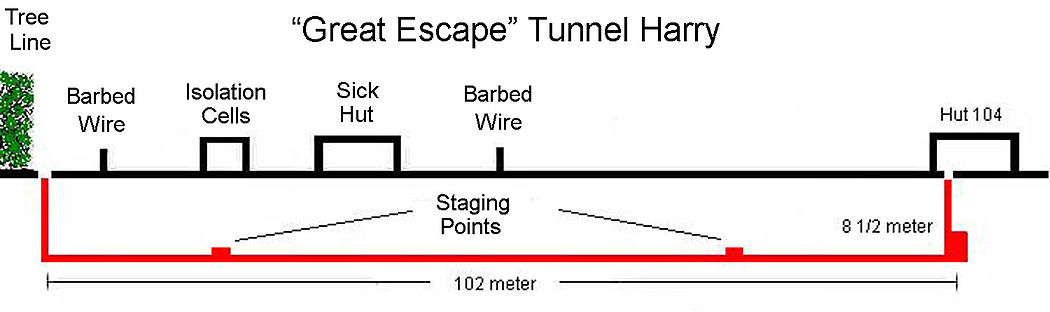

Background

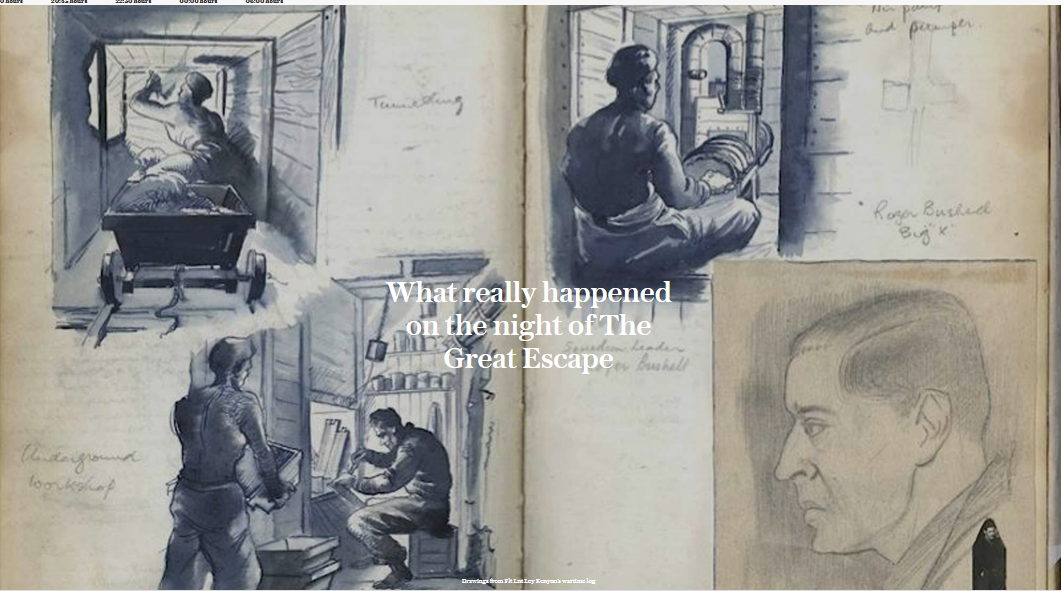

In March 1943, Royal Air Force Squadron Leader Roger Bushell conceived a plan for a mass escape from the North Compound, which took place on the night of 24/25 March 1944. He was being held with the other British and Commonwealth airmen and he was in command of the Escape Committee that managed all escape opportunities from the north compound. Falling back on his legal background to represent his scheme, Bushell called a meeting of the Escape Committee to advocate for his plan.

“Everyone here in this room is living on borrowed time. By rights we should all be dead! The only reason that God allowed us this extra ration of life is so we can make life hell for the Hun … In North Compound we are concentrating our efforts on completing and escaping through one master tunnel. No private-enterprise tunnels allowed. Three bloody deep, bloody long tunnels will be dug – Tom, Dick and Harry. One will succeed!”

Herbert Massey, as senior British officer, authorised the escape attempt which would have good chance of success; in fact, the simultaneous digging of three tunnels would become an advantage if any one of them was discovered, because the guards would scarcely imagine that another two were well underway. The most radical aspect of the plan was not the scale of the construction, but the number of men intended to pass through the tunnels. While previous attempts had involved up to 20 men, in this case Bushell was proposing to get over 200 out, all wearing civilian clothes and some with forged papers and escape equipment. As this escape attempt was unprecedented in size, it would require unparalleled organisation; as the mastermind of the Great Escape, Roger Bushell inherited the codename of “Big X”. More than 600 prisoners were involved in the construction of the tunnels.

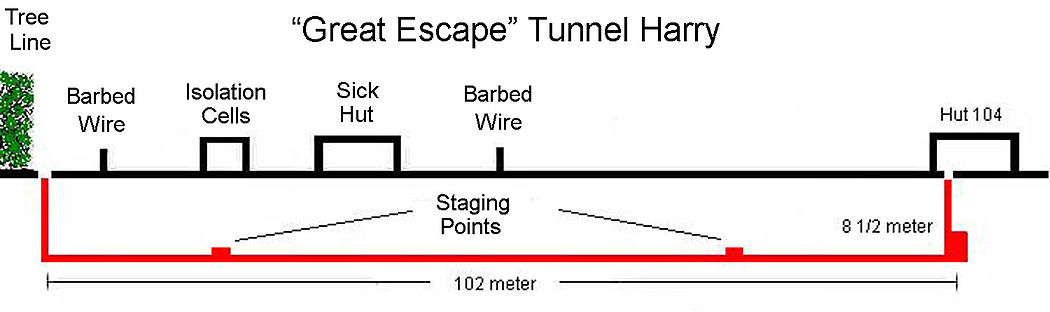

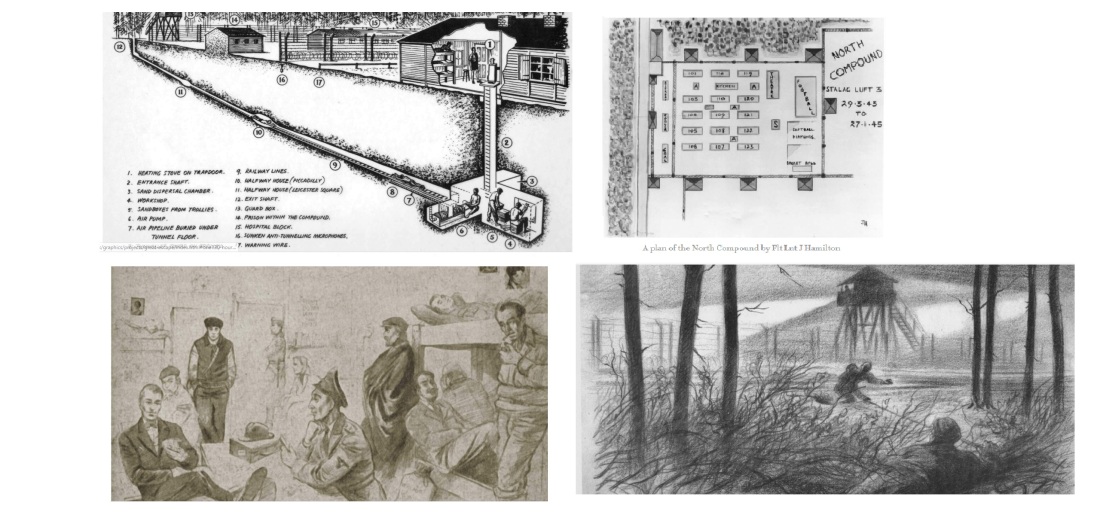

The tunnels

Three tunnels, Tom, Dick, and Harry were dug for the escape. The operation was so secretive that everyone was to refer to each tunnel by its name. Bushell took this so seriously that he threatened to court-martial anyone who even uttered the word “tunnel”.

Tom began in a darkened corner next to a stove chimney in hut 123 and extended west into the forest. It was found by the Germans and dynamited.

Dick’s entrance was hidden in a drain sump in the washroom of hut 122 and had the most secure trap door. It was to go in the same direction as Tom and the prisoners decided that the hut would not be a suspected tunnel site as it was further from the wire than the others. Dick was abandoned for escape purposes because the area where it would have surfaced was cleared for camp expansion. Dick was used to store soil and supplies and as a workshop.

Harry, which began in hut 104, went under the Vorlager (which contained the German administration area), sick hut and the isolation cells to emerge at the woods on the northern edge of the camp. The entrance to “Harry” was hidden under a stove. Ultimately used for the escape, it was discovered as the escape was in progress with only 76 of the planned 220 prisoners free. The Germans filled it with sewage and sand and sealed it with cement.

After the escape, the prisoners started digging another tunnel called George, but this was abandoned when the camp was evacuated.

Tunnel construction

The tunnels were very deep – about 9 m (30 ft) below the surface. They were very small, only 0.6 m (2 ft) square, though larger chambers were dug to house an air pump, a workshop and staging posts along each tunnel. The sandy walls were shored up with pieces of wood scavenged from all over the camp, much from the prisoners’ beds (of the twenty or so boards originally supporting each mattress, only about eight were left on each bed). Other wooden furniture was also scavenged.

End of “Harry”

End of “Harry” tunnel showing how close the exit was to the camp fence

“Harry”

Entrance of “Harry” showing outline of building

Other materials were also used, such as Klim tin cans that had held powdered milk supplied by the Red Cross for the prisoners. The metal in the cans could be fashioned into various tools and items such as scoops and lamps, fuelled by fat skimmed off soup served at the camp and collected in tiny tin vessels, with wicks made from worn clothing. The main use of the Klim tins was for the extensive ventilation ducting in all three tunnels.

As the tunnels grew longer, a number of technical innovations made the job easier and safer. A pump was built to push fresh air along the ducting, invented by Squadron Leader Bob Nelson of 37 Squadron. The pumps were built of odd items including pieces from the beds, hockey sticks and knapsacks, as well as the Klim tins.

The usual method of disposing of sand from all the digging was to scatter it discreetly on the surface. Small pouches made of towels or long underpants were attached inside the prisoners’ trousers; as they walked around, the sand could be scattered. Sometimes, they would dump sand into the small gardens they were allowed to tend. As one prisoner turned the soil, another would release sand while they both appeared to be in conversation. The prisoners wore greatcoats to conceal the bulges from the sand, and were referred to as “penguins” because of their supposed resemblance. In sunny months, sand could be carried outside and scattered in blankets used for sun bathing; more than 200 were used to make an estimated 25,000 trips.

The Germans were aware that something was going on but failed to discover any of the tunnels until much later. To break up an escape attempt, nineteen of the top suspects were transferred without warning to Stalag VIIIC. Of those, only six had been involved with tunnel construction. One of these, a Canadian called Wally Floody, was actually originally in charge of digging and camouflage before his transfer.

Eventually the prisoners felt they could no longer dump sand above ground because the Germans became too efficient at catching them doing it. After “Dick”‘s planned exit point was covered by a new camp expansion, the decision was made to start filling it up. As the tunnel’s entrance was very well-hidden, “Dick” was also used as a storage room for items such as maps, postage stamps, forged travel permits, compasses and clothing. Some guards cooperated by supplying railway timetables, maps and many official papers so that they could be forged. Some genuine civilian clothes were obtained by bribing German staff with cigarettes, coffee or chocolate. These were used by escaping prisoners to travel from the camp more easily, especially by train.

The prisoners ran out of places to hide sand, and snow cover made it impractical to scatter it undetected. Under the seats in the theatre there was a large empty space but when it was built the prisoners had given their word not to misuse the materials; the parole system was regarded as inviolate. Internal “legal advice” was taken and the SBOs (Senior British Officers) decided that the completed building did not fall under the parole system. A seat in the back row was hinged and the sand dispersal problem solved.

German prison camps began to receive larger numbers of American prisoners. The Germans decided that new camps would be built specifically for U.S. airmen. To allow as many people to escape as possible, including the Americans, efforts on the remaining two tunnels increased. This drew attention from guards and in September 1943 the entrance to “Tom” became the 98th tunnel to be discovered in the camp; guards in the woods had seen sand being removed from the hut where it was located. Work on “Harry” ceased and did not resume until January 1944.

Tunnel “Harry” completed

“Harry” was finally ready in March 1944. By then the Americans, some of whom had worked on “Tom”, had been moved away; despite its portrayal in the Hollywood film, only one American, Major Johnnie Dodge, participated in the “Great Escape”. Previously, the attempt had been planned for the summer for its good weather, but in early 1944 the Gestapo visited the camp and ordered increased effort to detect escapes. Rather than risk waiting and having their tunnel discovered, Bushell ordered the attempt be made as soon as it was ready. Many Germans willingly helped in the escape itself. The film suggests that the forgers were able to make near-exact replicas of just about any pass that was used in Nazi Germany. In reality, the forgers received a great deal of assistance from Germans who lived many hundreds of miles away on the other side of the country. Several German guards, who were openly anti-Nazi, also willingly gave the prisoners items and assistance of any kind to aid their escape.

In their plan, of the 600 who had worked on the tunnels only 200 would be able to escape. The prisoners were separated into two groups. The first group of 100, called “serial offenders,” were guaranteed a place and included 30 who spoke German well or had a history of escapes, and an additional 70 considered to have put in the most work on the tunnels. The second group, considered to have much less chance of success, was chosen by drawing lots; called “hard-arsers”, they would have to travel by night as they spoke little or no German and were only equipped with the most basic fake papers and equipment.

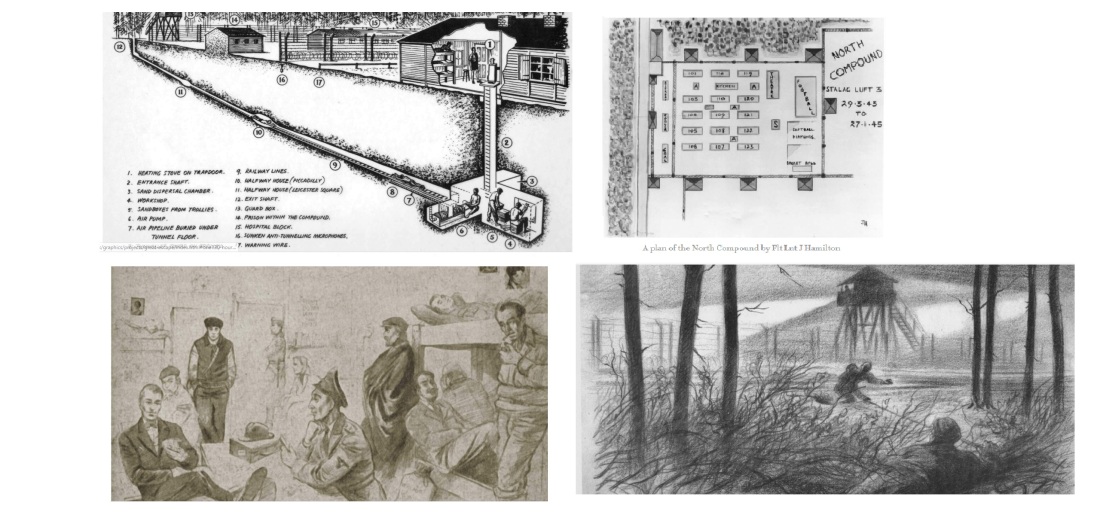

The prisoners waited about a week for a moonless night, and on Friday 24 March the escape attempt began. As night fell, those allocated a place moved to Hut 104. Unfortunately for the prisoners, the exit trap door of Harry was frozen solid and freeing it delayed the escape for an hour and a half. Then it was discovered that the tunnel had come up short of the nearby forest; at 10.30 p.m. the first man out emerged just short of the tree line close to a guard tower. (According to Alan Burgess, in his book The Longest Tunnel, the tunnel reached the forest, as planned, but the first few trees were too sparse to provide adequate cover). As the temperature was below freezing and there was snow on the ground, a dark trail would be created by crawling to cover. To avoid being seen by the sentries, the escapes were reduced to about ten per hour, rather than the one every minute that had been planned. Word was eventually sent back that no-one issued with a number above 100 would be able to get away before daylight. As they would be shot if caught trying to return to their own barracks, these men changed back into their own uniforms and got some sleep. An air raid then caused the camp’s (and the tunnel’s) electric lighting to be shut down, slowing the escape even more. At around 1 a.m., the tunnel collapsed and had to be repaired.

Despite these problems, 76 men crawled through to freedom, until at 4:55 a.m. on 25 March, the 77th man was spotted emerging by one of the guards. Those already in the trees began running, while a New Zealand Squadron Leader Leonard Henry Trent VC who had just reached the tree line stood up and surrendered. The guards had no idea where the tunnel entrance was, so they began searching the huts, giving men time to burn their fake papers. Hut 104 was one of the last to be searched, and despite using dogs the guards were unable to find the entrance. Finally, German guard Charlie Pilz crawled back through the tunnel but found himself trapped at the camp end; he began calling for help and the prisoners opened the entrance to let him out, finally revealing its location.

An early problem for the escapees was that most were unable to find the way into the railway station, until daylight revealed it was in a recess of the side wall to an underground pedestrian tunnel. Consequently, many of them missed their night time trains, and decided either to walk across country or wait on the platform in daylight. Another unanticipated problem was that this was the coldest March for thirty years, with snow up to five feet deep, so the escapees had no option but to leave the cover of woods and fields and stay on the roads.

Murders of escapees

Nationalities of the 50 executed prisoners

20 British

6 Canadian

6 Polish

5 Australian

3 South African

2 New Zealander

2 Norwegian

1 Argentinian

1 Belgian

1 Czechoslovak

1 French

1 Greek

1 Lithuanian

Following the escape, the Germans made an inventory of the camp and uncovered how extensive the operation had been. Four thousand bed boards had gone missing, as well as 90 complete double bunk beds, 635 mattresses, 192 bed covers, 161 pillow cases, 52 twenty-man tables, 10 single tables, 34 chairs, 76 benches, 1,212 bed bolsters, 1,370 beading battens, 1219 knives, 478 spoons, 582 forks, 69 lamps, 246 water cans, 30 shovels, 300 m (1,000 ft) of electric wire, 180 m (600 ft) of rope, and 3,424 towels. 1,700 blankets had been used, along with more than 1,400 Klim cans. Electric cable had been stolen after being left unattended by German workers; because they had not reported the theft, they were executed by the Gestapo. Thereafter each bed was supplied with only nine bed boards, which were counted regularly by the guards.

Of 76 escapees, 73 were captured. Adolf Hitler initially wanted every recaptured officer to be shot. Hermann Göring, Field Marshal Keitel, Major-General Westhoff and Major-General Hans von Graevenitz (inspector in charge of war prisoners) pointed out to Hitler that a massacre might bring about reprisals to German pilots in Allied hands. Hitler agreed, but insisted “more than half” were to be shot, eventually ordering SS head Himmler to execute more than half of the escapees. Himmler passed the selection on to General Arthur Nebe, and fifty were executed singly or in pairs. Roger Bushell, the leader of the escape, was shot by Gestapo official Emil Schulz just outside Saarbrücken, Germany. Bob Nelson is said to have been spared by the Gestapo because they may have believed he was related to his namesake Admiral Nelson. His friend Dick Churchill was probably spared because of his surname, shared with the British Prime Minister.

Seventeen captured escapees were returned to Stalag Luft III.

Two captured escapees were sent to Colditz Castle, and four were sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where one quipped “the only way out of here is up the chimney.” They managed to tunnel out and escape three months later, although they were recaptured and returned; Two were subsequently sent to Oflag IV-C Colditz.

There were three successful escapees:

Per Bergsland, Norwegian pilot of No. 332 Squadron RAF, escapee #44

Jens Müller, Norwegian pilot of No. 331 Squadron RAF, escapee #43

Bram van der Stok, Dutch pilot of No. 41 Squadron RAF, escapee #18

Bergsland and Müller escaped together, and made it to neutral Sweden by train and boat with the help of friendly Swedish sailors. Van der Stok, granted one of the first slots by the Escape Committee due to his language and escape skills, travelled through much of occupied Europe with the help of the French Resistance before finding safety at a British consulate in Spain.

Aftermath

Memorial to “The Fifty” down the road toward Żagań.

The Gestapo investigated the escape and, whilst this uncovered no significant new information, the camp commandant, von Lindeiner-Wildau, was removed and threatened with court martial. Having feigned mental illness to avoid imprisonment, he was later wounded by Soviet troops advancing toward Berlin, while acting as second in command of an infantry unit. He surrendered to British forces as the war ended, and was a prisoner of war for two years at the prisoner of war camp known as the “London Cage”. He testified during the British SIB investigation concerning the Stalag Luft III murders. Originally one of Hermann Göring’s personal staff, after being refused retirement, von Lindeiner had been posted as Sagan commandant. He had followed the Geneva Accords concerning the treatment of POWs and had won the respect of the senior prisoners. He was repatriated in 1947 and died in 1963 aged 82.

On April 6, 1944 the new camp commandant Oberstleutnant Erich Cordes informed Massey that he had received official communication from the German High Command that 41 of the escapees had been shot while resisting arrest. Massey was himself repatriated on health grounds a few days later.

Over subsequent days, prisoners collated the names of 47 prisoners they considered to be unaccounted for. On 15 April (17 April in some sources) the new senior British officer, Group Captain Douglas Wilson (RAAF), surreptitiously passed a list of these names to an official visitor from the Swiss Red Cross.

Cordes was replaced soon afterwards by Oberst Werner Braune. Braune was appalled that so many escapees had been killed, and allowed the prisoners who remained there to build a memorial, to which he also contributed. (The memorial still stands at its original site.)

The British government learned of the deaths from a routine visit to the camp by Swiss authorities as the protecting power in May; the Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden announced the news to the House of Commons on 19 May 1944. Shortly afterwards the repatriated Massey arrived in Britain and briefed the Government regarding the fate of the escapees. Eden updated Parliament on 23 June, promising that, at the end of the war, those responsible would be brought to exemplary justice.

Post-war investigation and prosecutions

General Arthur Nebe, who is believed to have selected the airmen to be shot, was involved in the 20 July plot to kill Hitler and was executed by Nazi authorities in 1945.

After the war ended, Wg Cdr. Wilfred Bowes of the RAF Police Special Investigation Branch (SIB) began to research the Great Escape and launched a manhunt for German personnel considered responsible for killing escapees. As a result, several former Gestapo and military personnel were convicted of war crimes.

Colonel Telford Taylor was the US prosecutor in the German High Command case at the Nuremberg Trials. The indictment called for the General Staff of the Army and the High Command of the German Armed Forces to be considered criminal organisations; the witnesses were several of the surviving German field marshals and their staff officers. One of the crimes charged was of the murder of the fifty. Colonel of the Luftwaffe Bernd von Brauchitsch, who served on the staff of Reich Marshal Hermann Göring, was interrogated by Captain Horace Hahn about the murders. Several Gestapo officers responsible for the murders were executed or imprisoned.

Survivors

Flight Lieutenant Bernard “Pop” Green, RAF was one of the escapees who was captured by the Germans and sent back to Stalag Luft III. He survived the war and returned home to Buckinghamshire. He died November 2, 1971. Green was the oldest person to be involved in the escape, 56 years old and born in 1887. His grandson Lawrence Green wrote a book about him in 2012 entitled Great War to Great Escape: The Two Wars of Flight Lieutenant Bernard ‘Pop’ Green MC.

Jack Harrison, who was one of the 200 men of the Great Escape, died on 4 June 2010, at the age of 97.

Les Broderick, who kept watch over the entry of the “Dick” tunnel, died on 8 April 2013 aged 91. He was in a group of three who had escaped out of the “Harry” tunnel but were recaptured when a cottage they had hoped to rest in turned out to be full of soldiers.

Ken Rees, a digger, was in the tunnel when the escape was discovered. He later lived in North Wales and died at age 93 on 30 August 2014. His book is called Lie in the Dark and Listen.

Gordon King of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, had been number 141 to escape and operated the pump to send air into the tunnel. Speaking candidly of his low number and resulting inability to get out of the tunnel that night, he said he considered himself fortunate. King had been shot down over Germany in 1943 and spent the rest of the war as a prisoner. He participated in the Battle Scars television series in his home town of Edmonton.

Jack Lyon, number 79 on the roster, celebrated his 100th birthday in 2017. He died on 12 March 2019, aged 101.

Paul Royle, a Bristol Blenheim pilot, was interviewed in March 2014 as part of the 70th anniversary of the escape, living in Perth, Australia at the age of 100. He downplayed the significance of the escape and did not claim that he did anything extraordinary, saying: “While we all hoped for the future we were lucky to get the future. We eventually defeated the Germans and that was that.” Royle died, aged 101, in August 2015.

Dick Churchill was the last surviving of the 76 escapees before his death on 15 February 2019; then an RAF Squadron Leader, he was among the 23 not executed by the Nazis. Churchill, a Handley Page Hampden bomber pilot, was discovered after the escape hiding in a hay loft. In a 2014 interview at the age of 94, he said he was fairly certain that he had been spared execution because his captors thought he might be related to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Charles Clarke was an RAF officer who served as a bomb aimer. After his Lancaster bomber crashed, he was captured and sent to Stalag Luft III; arriving weeks before the Great Escape. He did not take part in the escape itself, but had helped to forge papers and acted as a “watcher”. He later took part in the forced march, before being liberated. He remained in the RAF after the war, reaching the rank of air commodore. He returned to the camp in later life and helped build a replica of Hut 104 (where the Great Escape tunnel started). He also retraced the forced march on each anniversary. He died on 7 May 2019.

Note

The Great Escape occurred four days later on March 24th. (link to article)

Decades of research and extensive interviews with some 150 survivors shed new light on the wartime story that gripped the world.

By Charles Rollings, (edited by Joe Shute) Tuesday 22 March 2016

About Foss Boulton (source Facebook https://www.facebook.com/RCAF.ARC/)

Photo: S/L Foss Boulton (left), who was a prisoner at Stalag Luft III, describes his experiences to S/L R.A. Buckham in 1944. They were serving in the same squadron when Boulton was shot down in May 1943. DND Archives.

S/L Foss Boulton

Arrived in UK by plane, 8 April 1942. Attended No.57 OTU, 28 April to 4 August 1942; No.416 Squadron, 14 August to 30 August 1942; No.402 Squadron, 30 August to 20 December 1942; No.416 Squadron, 8 January to 13 May 1943 – shot down by flak while escorting Forts to Amiens; wounded in left arm, back and head; baled out at 26,000 feet; POW at Stalag Luft III (Where the escapees were executed by shooting or wire noose in a notorious war crime); repatriated to Britain, 28 May 1944; returned to Canada and commanded No.3 Release Centre, 9 December 1944 to 31 March 1946; released 6 May 1946.

Flying Officer, 18 May 1940;

Flight Lieutenant, 15 August 1941;

Squadron Leader, 8 January 1943;

Wing Commander, 1 March 1945.

Victories as follows:

19 August 1942, one Ju.88 damaged, Dieppe;

6 September 1942, one FW.190 damaged, Meaulte;

3 February 1943, one FW.190 probably destroyed, St.Omer;

3 April 1943, one FW.190 destroyed, Le Touquet;

5 April 1943, one FW.190 damaged west of Ghent;

17 April 1943, one Bf.109F destroyed north of Dieppe;

20 April 1943, one FW.190 destroyed, Dieppe coast;

3 May 1943, one FW.190 destroyed, Samer;

13 May 1943, one FW.190 destroyed and one FW.190 damaged.

Credited ‘at least four’.

Sqn Ldr Foss Henry Boulton

If you wish to contact us, please leave a comment or fill out this form below.